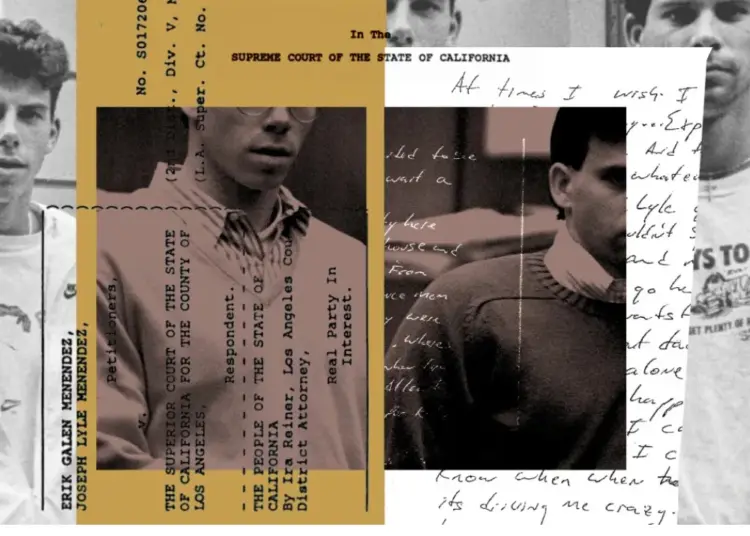

I was a practicing psychotherapist in Los Angeles when Lyle and Eric Menendez Brothers killed their parents in 1989. The headlines shouted the horrific act for days.

The brothers showed up in the news recently as they seek to be resentenced after 35 years in prison.

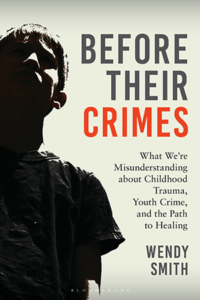

Having just written a book on this topic, Before Their Crimes: What We’re Misunderstanding About Childhood Trauma, Youth Crime, and the Path to Healing, to be published in November, I was moved to watch the documentary and the Netflix series about them.

Their wrenching description of sexual abuse echoed some of the experiences of the men and women I interviewed for my book. They too served long prison sentences for crimes they committed when they were teenagers, including murder and attempted murder. Of the 20 people whose stories are told in my book, eight were sexually abused. Five of the eight killed someone they knew. One killed a family member. The Menendez brothers could have been in my book.

Thousands of children are abused and do not kill their parents. When Lyle and Eric Menendez killed theirs, some people saw them as monsters who just wanted their parents’ money. Even now, 35 years later, the brutality of their crime and the shattering of the most basic taboo causes many people to feel they should remain locked up forever.

My interviews showed me what happened to kids before their crimes. I learned that murder and attempted murder inevitably sat atop a mountain of some kind of child maltreatment, loss, rage, and grief. In every case, there was no available adult in the picture to buffer traumatic events and avert moments of tragic violence.

Unfortunately for the Menendez Brothers, their trials and sentencing took place before researcher V.J. Felitti and his colleagues published their groundbreaking study of the impact of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) on long-term health outcomes in 1998. A randomized group of 9508 patients insured through Kaiser Permanente answered a survey about childhood experiences of physical, psychological or sexual abuse; substance abuse or mental illness of a parent, domestic violence in their home, and imprisonment of any household member. Over half reported at least one of these experiences and a quarter reported more than two.

From that study, we learned that problematic experiences in childhood were much more common than we thought. But that wasn’t all: we also learned that the damage caused stays with you. The more adverse childhood experiences you have, the more likely you are to have serious physical illnesses and emotional problems, use injectable drugs, attempt suicide, be unemployed, or have income below the poverty level. Children with more ACEs are more likely to be serious or violent offenders than those who don’t. The Menendez Brothers had three ACEs by my count: physical, emotional, and sexual abuse.

Both brothers were sexually abused by their father, beginning at age six, and continuing, in Eric’s case, up to the time of the murders. As a small child, Eric was made to do physically dangerous things to “toughen him up.” Forcing Lyle to view his premature baldness as something awful that must be hidden was emotionally abusive, as was the intense, unrelenting pressure to win no matter what, in sports and in life, and the withering verbal assaults when they lost or failed. Their childhood needs for love and tenderness were subverted into painful, confusing sexual acts. And while the Menendez brothers grew up amid social and economic privilege, that is no protection from abuse.

Sexual abusers demand secrecy, often by using threats, making it difficult for victims to seek help. There is some evidence that the Menendez boys told family members, or in Eric’s case, made attempts to run away as a child, but their mother, like so very many mothers in this situation, either could not bring herself to believe it, or simply refused to provide protection.

There is another formidable barrier to getting help—the acute, unbearable shame that sexual abuse engenders, especially in boys. The shame was so great for Lyle that he hoped never to reveal this part of their lives. Erik seemed crushed by shame and self-doubt and could not contain the secret.

The teen-aged brain is different from the adult brain. We used to think that the most important brain development concluded during adolescence, but now we know that key parts of the brain involving decision-making and judgment continue to develop until well into the twenties. At Eric’s age of 18, or Lyle’s of 21, you are much more influenced by sensation and reward centers in the brain, and much less able to consider the future consequences of your actions and restrain your impulses.

Since 1996, when the Menendez brothers were sentenced to life without parole, the fact of the incomplete development of the ‘executive’ functions (decision-making) in teen brains led to sweeping changes in sentencing laws. Life sentences without the possibility of parole for people under 18 have now been banned in 27 states. In California, the requirement for ‘youth offender parole hearings’ for those who committed their crimes when they were under age 18 was enacted in 2013, and the age limit was extended to 25 in 2018. Youth offender parole hearings take into account age and circumstances (including childhood trauma) at the time of the crime.

We can never know all the reasons why Lyle and Eric Menendez made the choices they did. I believe that years of abuse, devaluation, and shaming led to hopelessness and rage. They had received little from either parent that felt like love. During episodes of sexual abuse, they were functionally and emotionally abandoned by both parents. They could not trust their parents; they say they feared for their own lives once Lyle confronted his father about the continued abuse of Eric.

A woman I interviewed who was involved in the murder of a family member had lost her mother at age three, after which she lived with her grandmother. When she was ten, her uncle began to abuse her sexually. She told her grandmother, yet she was repeatedly left alone with her uncle. At the age of 16, she was present as her boyfriend killed her grandmother. For her, as for the Menendez brothers, the hurt and rage of victimization at the hands of people who should have loved and protected them, erupted in murder. In those deadly moments, it looked to them like the only solution to an unending problem.

The Menendez brothers were granted the possibility of a consideration of resentencing, but Nathan Hochman, the newly elected Angeles District Attorney, decided to take another look. He opposed resentencing, saying the brothers should remain in prison because they lied so many times and did not recant sufficiently. Their attorneys say he should be recused from the case because he is biased. A hearing is scheduled for May 9.

The Menendez brothers did lie, out of fear and, I believe, out of shame. Shame is the most primitive and powerful of emotions; it is often at the root of deception. From all appearances, the adults that Eric and Lyle have become are engaged in acts that improve the lives of others.

We have knowledge about brain development and the impact of trauma that we didn’t have 35 years ago, and youth offender laws have changed in response. After 35 years in prison, should the Menendez brothers be further penalized for what we didn’t know in 1996? We don’t lock up youthful offenders and throw away the key as we once did. Lyle and Eric Menendez deserve reconsideration of their life sentences.

Discover why the Menendez brothers’ case demands a second look—read the full feature now in IMPAAKT, the Top Business Magazine driving social impact.

Wendy Smith

Wendy Smith